How can we figure out what is going on inside a cell at any given moment? One thing that tells us a lot about which genes in a cell are being expressed — what the cell is up to, in other words — is the nature of the proteins that the cell is making. If we know that a cell engaged in some particular activity or process, we want to know what proteins are present in the cell, so that we can figure out what those proteins are for. Or, we can ask the same question from another direction: what do the proteins that are present in a cell at a given instant tell us about what the cell is doing?

Proteins are large, complex molecules made up of long chains of amino acids folded in and around themselves. They are the biochemical tools that cells use to get things done. There are many different types with different roles. Antibodies are proteins, for example, as are most enzymes. Proteins can also act as messengers, transmitting signals, or they can act as freight-carriers, moving atoms and smaller molecules around inside and between cells in an organism.

What are the practical applications of understanding the relationship between specific proteins and specific functions in the cell? For one thing, if we know which proteins are involved in a specific process, in which order, and whether and how they are modified in the process, this helps us understand the process better. Steve Blose, a biologist who came to Protein Databases, Inc., as chief scientist and later became president and CEO, describes how in the 1970s, after he finished his Ph.D. at Penn, he came to CSHL to work on “the cell biology of cancer cells.” At that time, researchers had observed “that non-muscle cells could crawl around using the proteins of muscles.” In cases of “metastatic cancer, and things like that, the cells could crawl around because they were actually employing the same proteins that were in our muscle.” Understanding which proteins were present in cells helped understand what those cells were doing and how they were doing it.

Understanding which proteins are involved in a given process within a cell also points us to various possibilities for interrupting this process or for encouraging or accelerating it, depending on what we want the cell to do. Adding or removing proteins from a cell allows for a kind of remote control from the outside — this, more or less, is what pharmaceutical products do. (In our story about AGI, for example, you can read about a biotech pharmaceutical product, Dimericine, whose active ingredient was a protein, an enzyme specifically, that corrects damage to DNA strands. Had researchers not known that this type of enzyme carries out a specific task on DNA, they wouldn’t have been able to develop the drug.)

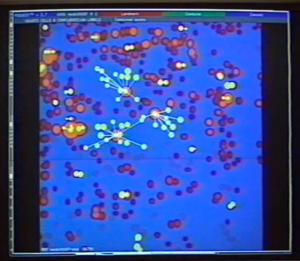

But tens of thousands of proteins can be expressed in a living cell. What is the best way to identify them — and how do we keep track of them all? In the late 1970s, a scientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Jim Garrels, was hard at work on a way of doing this. Jim’s idea was based on an existing method, gel electrophoresis. As PDI explained later in a press release, “electrophoresis is a method for separating a complex biological mixture of proteins.” The proteins are run through a gel, and an electric current is then applied to the gel. The electricity causes the proteins in the gel to separate according to specific characteristics they have. Previously, scientists had been able to do one dimensional gel electrophoresis, which separated molecules out according to their size, and “could resolve a maximum of about 50 different proteins. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, which was developed in 1975, separates molecules according to both size and electrical charge. Each protein present in a cell extract leaves its own distinctive spot on the gel; more than 2,000 proteins can be resolved in a single trial. Because of this exquisite sensitivity, 2-D gels contain far more information than can possibly be analyzed by visual observation” (James I. Garrels Collection: Protein Databases, Inc., June, 8, 1984 press release “CSHL Licenses 2D Gel Technology”). In other words, 2D gel electrophoresis produces a visual representation with two axes, one for size and one for electrical charge, and depending on their size and charge, proteins will appear as spots on this picture.

Jim Garrels did not invent 2D gel electrophoresis; the original idea was sketched out in a scientific paper published by Patrick O’Farrell in 1975. Jim was one of many people who used the technique and as a postdoc at the Salk Institute in California, he worked on refining it. “The laboratories there were very spacious and well funded and there was good equipment. And so that’s when the 2D gel electrophoresis appeared on the scene. I’d been doing 1D gels for a while, and I saw immediately the application of that. So I started to work on that and scale up the initial paper of the 2D gels that had come out. And there was, well, I was able to build some equipment, scale it up, make it larger, make it a little bit more automated and refine the technique quite a lot through making it more higher resolution and be able to run a lot of these at the same time.” Most importantly for the history of PDI, he came up with a way of analyzing and making extensive practical use of the information the method provided.

What was this method? First of all, it was necessary to make use of the magic of the atom. The use of radioactive isotopes in biological research is common now and it was common back in the 1970s. Cells can be grown in media with radioisotopes of some atom present in living cells (PDI’s method used S-35 methionine, an isotope of sulphur). The cells incorporate the radioisotopes and as a result all the proteins in the cell will be mildly radioactive. If you apply the 2D gel electrophoresis technique to proteins produced in this way, you get a not just a gel with a pattern of spots, but a gel with a pattern of radioactive spots. If you apply a sheet of photographic film to this gel, you wind up with a permanent image of this pattern of spots which you can analyze and compare to other such images.

But how do you analyze such an image? As the press release cited above points out, there are too many spots of too many different sizes to analyze with the naked eye. And if you have hundreds or thousands of such images, there is no way to make sense of them without analytical software.

It was precisely this software that PDI provided. Jim Garrels had done a lot of programming work in the past. His background was in phyics as well as biology and he had a longstanding interest in what computers could do for biology. (This was unusual at the time. “Back then,” he explains, “biologists didn’t use computers. That was thought to be something for the physical scientists or maybe business, but biologists had no need, and most people would just scoff at the thought of a computer, especially one on your desk. It didn’t make sense.”) Jim demonstrated, as his CSHL colleague and PDI co-founder Bob Franza describes, “that you could characterize these spots in a way that would allow for analysis,” and went on to write the software to do this. Bob relates how Garrels “spent years and years and years on that software, but he also set up a physical lab” in the McClintock building at CSHL, “where these gels were being run every day. It was a fairly industrial approach, small scale to doing 20 a day. The idea behind Protein Databases was to take that to a different level.” Franza saw fairly soon that there was potential in this idea “which was not going to materialize in an academic environment.”

But what precisely would be PDI’s business model? It took a while, and a little bit of trial and error, to work this out. Steve Blose describes his and his colleagues’ initial thoughts about how the technology could revolutionize pharmaceutical research: “it was in an era when science was fairly provincial. You were looking for a single druggable molecule. You weren’t looking at the total picture” of all the things that were going on in a cell. But the technology and software that he and his colleagues now had “was showing the total picture of all the interactions that would be going on in normal and abnormal cells…The technology could show you all the proteins that were being expressed. It could show you the protein half-lives, how fast they turn over. It could show you the modifications on the proteins…You could show all this in one shot, and then you could compare various experimental protocols, normal cells, cancer cells, and so on.” This created an extremely complex image. But “the software that Garrels designed reduced it down so that it could be digestible, so that you could say, for example, ‘Show me the top five proteins that are affected when a cell is transformed by [the tumor-causing virus] SV40,”…and the system could show that. No other system at that time was able to do that, and because it was” before researchers had the tools to sequence DNA quickly and easily, “they weren’t running DNA sequences or looking at the RNA expression.” The technology offered a glimpse that no other method at the time could match into which molecules were doing what inside a living cell.

PDI’s founders imagined the business developing in several different directions. They intended to accumulate data and create a massive database of proteins characterized through the 2D gel electrophoresis method and their software analysis. This would be valuable to researchers, as Steve Blose explained, because if you were faced with a protein in the course of your research that you could not identify, “you could look up your protein, and see what it was.” You could ship PDI a sample and “get good gels and answers back.” PDI also sold the software and machinery that they used, so that researchers could do the analysis themselves. At the time, “we thought that the information business,” running gels for people to identify proteins, “was going to be the most lucrative because people pay for information at a high margin.”

And there was reason to believe that this was the case. PDI’s story here intersects with that of Helicon Therapeutics. Steve tells the story of how they assisted memory researcher Eric Kandel in identifying proteins crucial to the formation of long-term memory. The core of the discovery came not from research on DNA or RNA, but from the identification of proteins:

Steve Blose, interviewed via Zoom June 1, 2023

Interviewer: Antoinette Sutto

Steve: “At that time, a famous neuroscientist at Columbia University, Eric Kandel, came to us, and he was part of the Howard Hughes Institute and still is, I believe. He had heard from Jim Watson, because they were friends, about this new technology. Kandel came to us and said, “We want to run protein specimens on the model system called aplasia, determine what are the proteins for long-term memory or long-term potentiation are. We can’t seem to find it through the DNA analysis or the mRNA expression. So we’re going to try proteins as well.”

Kandel’s group ran a series of gels over time, and they had the aplasia that were the control— that were not stimulated, and the aplasia that were stimulated that had the long-term memory remembrance of the stimulation. With that technology, they discovered– I’ve forgotten how many. I think four proteins that were upregulated in long-term memory. We were excited because it sort of beat out the DNA and RNA side, the nucleic acid side.

Kandel published that work in Cell, or I guess it was in Cell. Then later, when he got the Nobel Prize for discovery of long-term potentiation or long-term memory, I wrote to one of his colleagues who was in the lab at the time and just said, “Was the discovery that was made on the gel, the 2D system, the lynchpin?” The answer was yes. He needed those proteins. They figured it out what are the proteins, they had them sequenced, they found the genes, but it came from the protein side.”

“This technology in its early stages was invaluable to the first biotech company in the world, Genentech. Genentech showed you could clone the gene for tissue plasminogen activator, TPA, and that that protein could be used in heart attacks. You could shoot it into the blood vessel and it would dissolve the clot, so it’s a lifesaver.

In the early days, Genentech was expressing this protein in bacteria, in E. coli. The product that was made from that didn’t work very well. They knew of Jim Watson, and they knew of Cold Spring Harbor, and they knew of this new technology, 2D gel electrophoresis.

Genentech came to Protein Databases and said, “What’s wrong with this protein?” What we did is we ran it on the 2D gel system, and then we compared that TPA to what was circulating in the human serum. What we found is that the TPA that’s circulating in the human serum had six charges to it, glycosylated charges, but what was made in bacteria had none.

The synthesized TPA failed to have the glycosylated charged residues. Genentech said, “Okay, we’re going to then put the gene into mammalian cells, Chinese hamster ovary cells, CHO cells. Because those cells have a Golgi apparatus, they will glycosylate the protein properly.” When they did that, voilà, it worked. Protein Databases had a big sell. We solved the main problem for Genentech. We thought we were so famous. Wow. They paid us some money, we’re going to get recurring business, but it was a one-off because what they got from us was the information. They didn’t need to run the gels anymore because they got the answer.”

PDI, in other words, was able to figure out why a protein that Genentech was producing for pharmaceutical purposes was not doing what Genentech’s researchers expected it to do.

PDI’s technology had solved an important problem for Genentech, but this did not turn into a long-term business relationship. Once Genentech had the solution to the problem, they didn’t need anything further from PDI.

Another challenge, and perhaps a more fundamental one, that PDI faced in the 1980s and 1990s was the growth of DNA sequencing. At this time, PDI was doing well. Steve Blose describes how “we got this technology into the international scene. We were selling it in Japan and Europe, all over the place.” They were working with pharmaceutical companies, and “we had also engaged with a Japanese company, Toyobo, which was essentially a biochemical textile company that was moving into biotech.”

But “over time, the evolution of the biotech world was to go more towards DNA sequencing because the sequencers were now getting faster” and the process was easier to perform. “PCR came out, so you can amplify up the genes that you need to see. The protein side took” second place. “If you weren’t doing DNA, you weren’t in the game, and yet we would go to [drug developers] and say, ‘But the druggable targets, 98% of the drugs in the market target proteins and enzymes that are proteins. Why wouldn’t you want to go after druggable targets?’ … Our advisors tell us, ‘No, you’ve got to have the genes because that’s got to be it.’ I said, ‘Well, but you don’t know if the genes are on or off…How do you know that?’ The other thing that you won’t know from gene expression or the mRNA analysis is whether proteins were modified, post-translation, especially phosphorylation, which was a switch on and off.” With DNA analysis alone, you’re missing a lot of pertinent information. But with all the excitement around improvements in DNA sequencing, it was more difficult to get people excited about proteins. And in addition to DNA sequencing taking up more and more of the limelight, there was a technical challenge. “The two-dimensional gel technology is a very complicated thing. It was not automated. You couldn’t drop a sample in the machine and have it generate images, you had to do a lot of manual work.” It took a week, more or less, to get a sample through the process. “A lot of people said, ‘Geez, that’s an eternity,’ but there was no other way to do it.” For a while, Steve says, “the clock was in our favor.” But as other technologies became faster and more reliable, and seemed to be able to address some of the same problems, PDI had a harder time making a case for what it had to offer.

In the end, Steve decided that PDI’s technology was better off as part of a larger biotech company. “I decided that the better thing to do with the Protein Database company was to put it in the hands of a major biotech company that supplies the research market. That was Bio-Rad Laboratories in Hercules, California. We took the company to Bio-Rad and they bought it, and then they actually hired me to run the recipient division of the technology… While I was at Bio-Rad, we continued to commercialize the technology with faster scanners, better software, and to keep it in the market. It was a real help because they had an international distribution system. Our small company just didn’t have that.”

The goal was to get and keep the technology out there and in use, solving problems. The best way to do this was to sell PDI to a larger firm with more and different resources. As we’ll see elsewhere in the exhibition, this life cycle from research to idea to small startup to success and finally to acquisition by a larger firm either locally or elsewhere is common among biotech startups. Is this desirable? That depends on your perspective. If your goal is to encourage the development of companies that will remain local and grow here on Long Island, it might not be. If your goal is to bring a specific discovery onto the market and get it into the hands of people who can use it, then it is.

Want to read more about how to encourage the growth of small biotech companies on LI? Read our story on the Stony Brook Center for Biotechnology.