Communication is a perennial challenge in the world of biotechnology. This is true for people with a research background who want to talk to venture capitalists, and for people from the world of business, real estate and finance, who may have unrealistic ideas about science. It was particularly the case in the early days of DNA manipulation, when the ability to slice and sequence and clone genes did not seem so far removed from magic. One Cold Spring Harbor Lab scientist turned biotech entrepreneur in the 80s and 90s recalled a lunchtime conversation with someone from a well-known New York investment firm who “thought that you could clone pork chops in trees with genes or something, and I’m going, ‘No, that’s not how it works.”‘

Scientists, too, are often missing information. As Glenn Prestwich, former director of SUNY Stony Brook’s Center for Biotechnology and himself a chemistry professor, puts it, “faculty are good at learning and listening to what they want to hear,” but convincing them that there may be other things that they need to learn, things they might not have thought of themselves, can be difficult.

In other words, a mutual education process has to take place. One of the main roles of the SUNY Stony Brook Center for Biotechnology is to act as an interface point between these two cultures. Whoever is in charge of this center has to play the role of translator or cultural liaison. They need to have a sense of where problems are likely to occur in the process of going from discovery to company, and how communication between scientists and investors is likely to break down.

How this works in practice and how simultaneously frustrating and rewarding this job can be comes to the fore in the story that Glenn tells about how he became director of Stony Brook’s Center of Biotechnology in the 1990s and what he learned in the process.

Glenn earned his Ph.D. at Stanford in 1974. This was during the period when recombinant DNA methods were being developed and a controversy was developing around the safety and ethics of experiments that cut and combined DNA from different sources. It was these very methods that laid the foundation for the biotechnology industry of the 1980s and 1990s. However, Glenn was a “pure organic chemist” interested in “insect biology and chemical ecology.” Recombinant DNA “wasn’t on the radar screen” for him.

His postdoctoral research, as part of a team based at Columbia University and Cornell University headed by Professors Koji Nakanishi and Jerry Meinwald, took him to Nairobi, Kenya, with a stop beforehand at Cornell, where he worked with Tom Eisner, an “amazing photographer” and insect biology colleague of Meinwald’s. Glenn was a natural products chemist, i.e. an organic chemist whose area of expertise is substances produced by natural organisms, and at Cornell he “learned how a natural products chemist can basically tag along behind a biologist and learn stuff” and “turned [himself] into the chemist who helps biologists.” In Kenya, it was hard to find projects for himself as a chemist because the material conditions in Nairobi at the time made it hard to run the equipment he needed to use. Biology, however, proved to be a different story. “What I was good at was going out and [doing] what nobody else could do, [which] was to go out to the forests, the rainforests, the coasts, and the savannahs, and hunt for bugs and be a friend, be a shadow chemist that goes along with the biologists.”

What was Glenn working on during his time as a “shadow chemist”? After a few false starts, he ended up working on termites, which turned out to involve some pretty “remarkable new molecules.” Biologists knew that termites used chemical signals to carry out all kinds of tasks, and Glenn more or less “made a career out of termite chemical defense chemistry” — what the molecules involved in this process were, and how they did what the termites needed them to do.

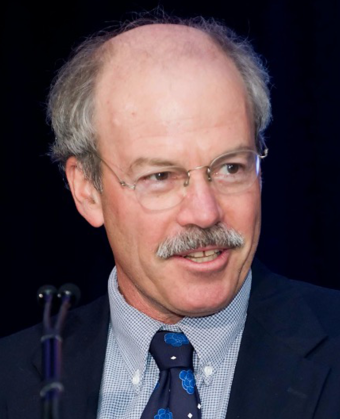

Glenn Prestwich, interviewed via Zoom on June 20, 2023

Interviewer: Antoinette Sutto

“The other thing was termites. Termites, there was a good community of termite researchers. They did ultrastructural work with scanning electron microscopes. They did behavioral stuff. They knew enough about chemistry to understand what a chemist could do to help them. They knew there were volatile signals involved in building behavior, and trail following, and food-finding, and nestmate recognition, and chemical defense. So all of a sudden I became their best friend. I trailed everywhere. Anywhere the termite people went, I went too. I would collect stuff and I would come back and I’d extract the termite soldier heads, and I’d purify compounds. I’d send them to Meinwald’s lab and I’d send some to [Koji] Nakanishi’s lab.

Some of the best crystallographers in the world worked on these structures and we published amazing new compounds that it took organic chemists 20 years to figure out how to synthesize. There were such remarkable new molecules. Basically, I made a career out of termite chemical defense chemistry. I found some termites were making these, basically, they’re poisons that were Michael acceptors and they were alkylating enzymes. The work resulted in a few years later in a two-author Science paper with my first graduate student, Stephen Spanton. We figured out how the termites actually defended themselves so that they didn’t get their proteins alkylated. It was great. In Africa, I also spent a lot of time because in the field, you need to do field assays to find, do the trail following.

One of the big ones that we did was there was a pheromone emitted by a queen termite that caused the workers to build a queen chamber, which is what protects the queen. It’s built at exactly the same distance from her cuticle all the way around. It has the shape of a queen, except it’s one to two centimeters away from her large body. How does that happen? We actually extracted the surface of a queen and started putting the extracts from the queen on filter paper that was moist. We fractionated them and it turns out to be palmitoleic acid which is a very unusual unsaturated 16-carbon acid. Not very common and it was only one compound — if it was two carbons longer, two carbons shorter it didn’t work. If you didn’t get the concentration right, it didn’t work. If it wasn’t moist, it didn’t work but if you put that on a glass rod with filter paper on it, the workers would build a queen chamber around the glass rod. It’s like yes, we did it! That was published in a review paper in Science magazine, and was the first chemically characterized termite building pheromone.”

But it’s a long way from these “remarkable molecules” in Kenya to being a “biotech guy,” as Glenn later put it, on Long Island. How did he get there?

The first step was a position at SUNY Stony Brook. Although he grew up in upstate New York, he “had escaped from New York to go to Caltech and Stanford, and I never really wanted to go back to New York at all. I was done with that but I figured it’s going to be a good place, Stony Brook. I was thinking it’s near the Poconos, it’s going to be a nice location, I’ll go down for the interview. It wasn’t until the professor that was interviewing me gave me the directions [that I realized where the place was]. He said, ‘you have to go over the Throgs Neck Bridge.’ I said to myself, oh crap — I’m going to Long Island.” But Long Island as it is isn’t necessarily the Long Island that comes to mind based on pop culture. “Then I realized you’d drive out, out, out, out, out. It’s not Long Island as you think of it from the movies. It was a really beautiful pastoral environment. That changed my attitude, and developed my entire future.” Glenn was deciding between the job offer from Stony Brook and another from a university in Miami, Florida. In the end, a combination of academic reputation and the ease of getting research funding led him to “take the Stony Brook offer, and they made it really quite a sweet deal.”

At Stony Brook, he continued his work on insects. He was soon faced with two problems, however. The first was that his work wasn’t getting the recognition he had hoped for. He wanted to “publish in higher-reputation journals. I was doing some pretty novel stuff and it was buried in these insect journals. There was a lot of selfish narcissism in there, but the creativity wasn’t being recognized and rewarded in the insect world by the people who were picking it up.”

At Stony Brook, he continued his work on insects. He was soon faced with two problems, however. The first was that his work wasn’t getting the recognition he had hoped for. He wanted to “publish in higher-reputation journals. I was doing some pretty novel stuff and it was buried in these insect journals. There was a lot of selfish narcissism in there, but the creativity wasn’t being recognized and rewarded in the insect world by the people who were picking it up.”

A second problem was funding. In the early 1980s, “the National Science Foundation’s entire funding mechanism for what they called Division of Applied Biology was eliminated. That meant that two-thirds of my grants went from a couple $100,000 a year to zero. That meant my research group of almost 30 became a research group of eight. I had to refocus.”

This was where the Center for Biotechnology entered the picture. It was relatively new at the time, and Glenn got to know the director, Dick Koehn, who also had a life sciences background. “He knew that I was doing all sorts of stuff at the interface between chemistry, biochemistry, and biology because he was an ecological molecular biology person looking at the genetics and population ecology of Mytilus edulis, which is the common Long Island mussel.” Dick Koehn and the Center were key to the pivot in Glenn’s career. “Dick’s Center helped me change my direction from working on all of the things that weren’t going so well. I needed a project to propose because the Center had these small grants that you could get a little bit of money and get started on some new project.”

Glenn ended up using experience he already had in photoaffinity labeling as a jumping-off point for a new project. Photo-affinity labeling is a technique to describe the interactions among small molecules, which is very useful for drug development among other things. Glenn had been using it for other purposes in his insect research, but when he talked with a Stony Brook colleague, a world-renowned neuroscientist named Solomon Snyder, Snyder told him about a neural signaling molecule that he was working on, IP3, that he wanted to know more about, and Glenn realized that he could put his experience in photo-affinity labeling to work here to find receptor proteins. The collaboration ended up being enormously successful. “We published these groundbreaking papers that just wide-opened the field… we just went crazy labeling all these things.”

This collaboration was part of two important shifts in Glenn’s career: his developing association with the Center for Biotechnology, and the transition into a different area of biochemistry, from insect work to lipid cell signaling. But it took a different project, likewise funded by Dick Koehn through the Center, to get him interested in patents, which were and remain key to the development of the biotech industry.

This project, was an exception to his research program at the time, but it turned out to be a good bet. It involved hyaluronic acid, which has a number of important medical applications. Glenn explains:

Glenn Prestwich, interviewed via Zoom on June 20, 2023

Interviewer: Antoinette Sutto

[Clip 2a]

Glenn: …As well as one other project that Dick funded from the Center, which was figuring out what to do, how to do chemical modifications of hyaluronic acid and study its receptors.

Antoinette: Why did he want to do that?

Glenn: They wanted to do that because I had industry funding in the late ’80s to start looking at hyaluronic acid because one of my Chinese students worked for a company in Massachusetts– former students had worked for a company in Woburn, Mass. He writes to me, he says, “I want to come back and get a Ph.D. My company will pay for everything, but they want me to work on hyaluronic acid.” I said, “What’s hyaluronic acid?” He says, “Well, it’s a long water-soluble polymer.” I said, “Stop there, you know my lab, we work on small lipids, not water-soluble polymers.”

He said, “Yes, but they’re paying for everything, and there’s chemistry that nobody knows how it works.” I said, ‘Okay, you got me now, so let’s do it.” He came to the lab. We started working on hyaluronic acid. Everything that we did, trying to show that the literature was right, proved that literature was wrong. And so everything we did was publishable and patentable. That’s when I got more interested in patents. We already had patents and patented some lipid stuff from the insect control work…..

[Clip 2b]

Antoinette: Hyaluronic acid. Is this the thing that’s found in rooster combs and it’s related to treating inflammation and use for drug delivery? I wanted to make sure I was marking the same thing in my notes as I was hearing from you.

Glenn: That’s right. At the time, what the interest was, was for making things that prevented post-surgical adhesions or could be injected into osteoarthritic joints, especially knees, to relieve the pressure, and would stay in the joint longer than natural HA. Which was rapidly degraded by hyaluronidases. Which were abundant in arthritic joints because that’s why you had an arthritic joint because your joints were degrading the hyaluronic acid in the synovial fluid because of the inflammation. There were two potential outcomes for that. To do that, they needed chemical modification technologies.

There were some that were out there but people weren’t having much luck. When I started looking at the chemistry of what reactions were published or in the patent literature, we would look at these things and we’d isolate the products, and they didn’t have the structures that were claimed. When we actually figured out what the structures were, we had new composition of matter that was surprising and unexpected and a method of making things and use. Everything was surprising and unexpected. It was a gold mine.

The work on hyaluronic acid had important medical applications. They had “new chemistry, new IP [intellectual property], the intellectual property on that is now owned by Anika Therapeutics and they’re still using it in three different products.”

Over the course of his time as a chemistry professor at Stony Brook in the 1980s, in other words, Glenn developed a relationship with the Center for Biotechnology, which funded several of his projects. He also explored new areas of research, some of which resulted in patentable work with biomedical applications.

All of this set the stage for him being, as he put it, “dragged kicking and screaming” into the role of the Center’s director in 1992 and becoming, at least part time, a “biotech guy.”

Glenn was on sabbatical at the University of Utah, working with a colleague there, Dale Poulter. At the end of his stay at Utah, “I was getting ready to get in the car to go on a rafting trip on the Colorado River. I get this phone call. ‘Dr. Prestwich, this is Tilden Edelstein,’ the SUNY Stony Brook provost at the time. He said, ‘I have a proposal for you. We want you to become the director of the Center for Biotechnology.’ I said, “You what?’ ‘Well, we want you to help us with the Center for Biotechnology. This is the thing that Dick Koehn has been running.’ I said, ‘Yes, I know the organization. That’s fantastic. Dick is good at administrative stuff.’ I’ve just spent 18 months on sabbatical in three different laboratories in three different countries learning all of this cool stuff, and I’m planning to come back to Stony Brook and expand my research group and do all this research. I said, ‘I don’t want your job. I don’t want to be an administrator. I’m a research scientist.’ “

Glenn’s initial reaction to the idea was that he was not the right person for this job and that he had no inclination to try to take on this kind of work — he’d rather being doing research. The provost told him to sleep on it, think it over, and come up with a list of what he would need if he decided he could accept the job. Glenn said he’d call him back in the morning. The next day, he talked to the provost again.

Glenn Prestwich, interviewed via Zoom on June 20, 2023

Interviewer: Antoinette Sutto

I called Provost Edelstein back and I say, “Okay. Well, I’m going to need this salary. I’m going to need a full-time postdoctoral research lieutenant for my laboratory of a high level, and I know who I want. I’m going to need a full-time somebody to maintain my laboratory logistics, and I have the right person. I just need to have her salary paid. I need this, I need this, I need this.”

He said, “Okay, done, done, done, done, done. You’ve got the job. By the way, you have to be here a week from Tuesday because you’re giving a presentation to the Lieutenant Governor.” [laughs] That was my introduction to the Center for Biotechnology.

Antoinette: “By the way…”

Glenn: –all while on a goddamn river rafting trip to negotiate a job that I didn’t want, then to be there a week and a half later. We had to tear across the country in the car after the river trip to get there in time to do this presentation. That’s when I learned about Books on Tape at the time, and I listened the entire trip. We hardly could stop driving for gas because we couldn’t put it down. We were listening to The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey’s classic novel of eco-terrorism.

When Glenn and his family got back to Stony Brook, he had about 36 hours to get the presentation together. But he did it.

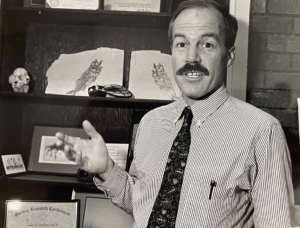

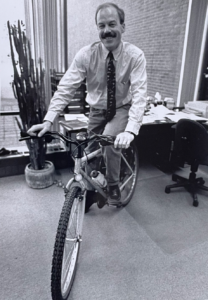

The new role involved more than just surprise presentations. He had to learn how to be a “biotech guy,” at least part time. Part of this involved becoming comfortable moving between two roles, in a pretty literal sense. He didn’t want to spend more than about half his time at the Center and made an effort to keep the two halves of his professional persona distinct. He taught his classes as a chemistry professor, then put on his bike clothes, biked across campus and then once in his office at the Center, “I put my nine-piece suit on and looked like a biotech guy. That was me going back and forth on a bicycle between nerd professor and biotech guy.” Being a biotech guy involved more than a suit. Diane Fabel, the Center’s operations director, gave him some direction: “she basically trained me to be a biotech guy. I give her an incredible amount of credit for my transformation from a lab geek professor to being somebody who had any sense at all about working with people in industry. Again, there was a lot more kicking and screaming involved.”

The new role involved more than just surprise presentations. He had to learn how to be a “biotech guy,” at least part time. Part of this involved becoming comfortable moving between two roles, in a pretty literal sense. He didn’t want to spend more than about half his time at the Center and made an effort to keep the two halves of his professional persona distinct. He taught his classes as a chemistry professor, then put on his bike clothes, biked across campus and then once in his office at the Center, “I put my nine-piece suit on and looked like a biotech guy. That was me going back and forth on a bicycle between nerd professor and biotech guy.” Being a biotech guy involved more than a suit. Diane Fabel, the Center’s operations director, gave him some direction: “she basically trained me to be a biotech guy. I give her an incredible amount of credit for my transformation from a lab geek professor to being somebody who had any sense at all about working with people in industry. Again, there was a lot more kicking and screaming involved.”

Glenn wasn’t enthusiastic about some aspects of the role. “I hated networking. I hated schmoozing at conferences. I hated business stuff, I hated putting on a suit on all the time.” But he was good at working with faculty. He didn’t see himself as “much of a relationship person,” but he learned how to be one in this context. One of the key things with other faculty members, as far as collaborations with industry was concerned, was “to get them on board and get them not just to be money acceptors, but to be partners. Not just to get the money and then it’s done, but to get the money, do the project, and then be part of the next step, the translation to something that had a commercial value and to be part of the whole process, and to train them as much as I could” in how to be entrepreneurs, “although I didn’t know much myself.” He “figured out how to make it work so that everybody got what they wanted,” and looking back, it was both worthwhile and fun, although not something that he necessarily wanted to do for the rest of his career.

Ultimately, Glenn’s interest in being a researcher outweighed his interest in donning the “nine piece suit” and continuing to schmooze. He got tired of being on the Long Island Expressway all the time instead of in the lab, and found he was getting tired of the Long Island / New York region in general. In 1996, he accepted a professorship in chemistry at the University of Utah.

Ultimately, Glenn’s interest in being a researcher outweighed his interest in donning the “nine piece suit” and continuing to schmooze. He got tired of being on the Long Island Expressway all the time instead of in the lab, and found he was getting tired of the Long Island / New York region in general. In 1996, he accepted a professorship in chemistry at the University of Utah.

Glenn’s career path from natural products chemist to director of Stony Brook’s Center for Biotechnology to chemistry professor again highlights the forces that can both push and pull a researcher into the field of biotechnology (and out of it again). Interest in the science itself and its applications is central, but there are other things too — the availability of funding, the desire for recognition, personal connections, and simply where you enjoy living and the kind of professional culture you are most at home in. His career also highlights the challenges of trying to bring scientists and people from industry together. Glenn himself got dragged “kicking and screaming” into the role of “biotech guy.” He had to put a lot of effort into winning over his colleagues, who were often at least as suspicious of the whole enterprise as he had been. Interfacing between two cultures is an enormous amount of work, and it’s work that often ends up being far less visible than a scientific breakthrough or a big IPO, even though it’s essential to building a viable biotech industry here on Long Island or anywhere else.

For more on the Stony Brook Center for Biotechnology, read our piece on the Center’s history and contribution to the growth of the biotech industry on Long Island.